FAMILY LAW- Re (Same-sex Relationship)-G(Children Residence Order)(Part Two) A Case of the emerging changing social and legal climate in relation to biological and the psychological parent

BRIEFS & MEMOS

Having discussed the law prior Re G, in the part one of this essay- captioned, “Same-sex Relationship And Child Law”, we would now turn our focus on Baroness Hale’s statement in Re G which has attracted this paper.

The significance of genetic parentage in a case of disputed residence-Re G

Before we establish any legal principles on genetic parenthood in relation to Baroness Hale’s statement , it is important to mention a statement made in Australia Family Court by Lindenmayer J in Hodak, Newman and Hodak[18]:

‘I am of the opinion that the fact of parenthood is to be regarded as an important and significant factor in considering which proposals better advance the welfare of the child. Such fact does not, however, establish a presumption in favour of the natural parent, nor generate a preferential position of the natural parent from which the Court commences its decision-making process…’

Having read Lindenmayer J’s statement and the above established arguments on parenthood, one may ask what at all is parenthood and what do we mean by ‘natural parent’?

It is important to note that there is a difference between a natural and legal parent. A mother of a child is the woman who gives birth to the child.[19] As Bainham would argue ‘pater est’ presumption attributes parentage to the mother’s husband unless and until it is rebutted[20]. In other words, there is a common law presumption of legitimacy that a child born to a married couple makes the husband the father of that child. This is however, rebuttable on proof of evidence.

Thus a father of a child born to an unmarried parent was not legally a ‘parent’ until Family Law Reform Act 1987 but was always the natural parent. The anonymous donor who donates his sperm or egg under the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990(HFEA 1990) is a natural progenitor of the child but not his legal parent(see sections 27 and 28). The husband or unmarried partner of a mother who gives birth as a result of donor insemination in a licensed clinic in UK is the legal parent, but may not be the natural parent [21]. The status of a legal parent gives those involved the parental responsibilities to bring and defend proceedings about the child’s welfare.

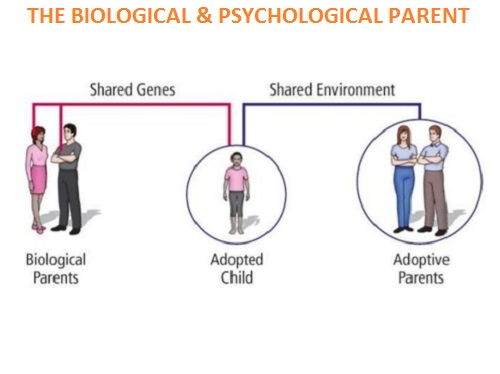

There are at least three ways of becoming a natural parent, this may be of an important factor in cases where the child’s welfare is at stake.

Firstly, genetic parenthood (gametes which produce child), this way of production is arguable of the benefit of the child knowing his origins and lineage- especially, the love and commitment that the child would gain from the grandparents.

Secondly, gestational parenthood, which means- the conceiving and bearing of the child- under s. 27 of HFEA 1990, the mother of the child is the woman who bears the child, not the one who provided the egg.

The third way is social and psychological parenthood: this is a relationship which develops through nurturing, feeding, socialising, educating and protecting the child. The term ‘psychological parent’ used by Baroness Hale in Re G, has been defined as;

‘… one who, on a continuous, day-to-day basis, through interaction, companionship, interplay, and mutuality, fulfils the child’s psychological needs for a parent, as well as the child’s physical needs. The psychological parent may be a biological, adoptive, foster or common law parent.’[22]

In most cases the natural mother combines all the three (genetic, gestational and psychological), and the natural father gets the status of genetic and psychological parenthood. And as Baroness Hales stated this is an important factor to bear.

Nevertheless, Mr. Ellis a donor-conceived person who gave evidence to the recent Joint Committee on the Human Tissue and Embryos (Draft) Bill stated that;

‘‘A man or woman whose gametes are not used to create a child should not be referred to as simply a “parent”. If that man or woman raises the child it should be made clear that the man or woman is an “adoptive parent” or a “step-parent”. Likewise, sperm or egg “donors” are never just donors. They are genetic parents. It is wrong that this legislation attempts to sever this relationship between parent and child.’’[23]

Judith Masson another critic on the other hand argues that;

‘There is “parenting by being” and “parenting by doing”. The latter functional approach to family relationships, which supports the notion of social parenthood, has gathered considerable ground in recent years. If it looks like a family it must be a family, if people behave in a “marriage-like” way they should be treated as if married (or if they are of the same sex, as civil partners) and, so the argument goes, if someone behaves as a parent he or she is a parent.’[24]

Clearly, the law on parenthood does not favour those who believe in in ‘genetics’ because the law does not necessarily take a medical definition on who a parent is. But gives ‘parent’ a legal definition, which is arguably, key in safeguarding the welfare of a child.

Drawing our attention back on Baroness Hale statement, her attention was arguably, on exploring what ‘natural parenthood’ meant and the weight which should be attached to it. She emphasised that although Re G involved a lesbian couple, the legal principles were of ‘universal application.’

Recognising J v C as the landmark case, she noted the ‘no presumption’ approach adopted by the Court and agreed with the comment which the Law Commission gave to clarify the law post J v C. There it seems like her Ladyship, was going to endorse the ‘no presumption’ approach. She made a U-turn and identified three distinct routes to ‘natural parenthood’ as mentioned previously. She then went on and accorded the status of natural parent to CW.

Given that CW was neither a legal nor a genetic parent and that CG had tried to deny her any parental status. Thorpe LJ appeared to be in agreement with this move. Nevertheless, her Ladyship in effect created what has been described as a parental hierarchy, meaning that in any dispute between genetic and psychological parents, the genetic parent effectively holds the trump card, but only in situations where the genetic parent is also a psychological parent.[25] Lord Nicholls and Lord Scott supported this concept.

Leanne Smith predicted that the case would have an effect on heterosexual families, not only where children were conceived by way of donor insemination and surrogacy, but also in cases where both parents were biological parents.[26]

Since Baroness Hale’s Judgment in Re G, three recent cases[27] all relying on Re G have demonstrated a shift back to the natural parent presumption in the Court of Appeal. The last of these, Re B(Residence: Second Appeal)[28], has now been overturned by the Supreme Court. The case involved a residence dispute between the father and the maternal grandmother of the child, with whom the child, H, born in December 2003 had lived throughout his 6 year life. Father was released from prison he remarried and wanted his son to reside with him.

The court objected this. He appealed against the decision and was ordered residence. The grandmother appealed and this was dismissed. In 2009, the Supreme Court re-instated the residence granted to the grandmother. Wall LJ noted that, the confusion lie between the principles relating to public as opposed to private law proceedings. The judge had commented that the reasoning in Re G was merely repetition of Lord Templeman’s speech in Re KD in a pre-Children Act public law case. And it is not only a misstatement of the law pre Re G, but also demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of Baroness Hale’s speech in Re G.[29]

SURVEY

Above all the confusion on the law on residence dispute, a survey was conducted to ascertain the view of a sample of 10 people, who were asked as to the importance of genetic parentage in scenarios involving different routes of parentage and the relationship a child may have with an adult who is not genetically related. The examples includes the conceiving of a child using a sperm donor(both anonymous and known), surrogacy to both hetrosexual and same-sex couples.

The findings of this survey was arguably not surprising in support of the argument presented in this piece, about 50% of those asked would consider a husband whose wife had conceived a child using an anonymous sperm donor as the father of the child.

On the other hand 50% disagreed with this, and would instead prefer to call him a social or adoptive parent. Interestingly about 80% of those asked would call an married man the father of a child conceived following an affair of his wife. The visible split of view was in the case of surrogacy involving hetrosexual and homosexual couples, 90% would call the surrogate mother the mother of the children in a hetrosexual relationship but only 40% would identify a man the father in a gay relationship.

Above all the split of views on how to call an adult’s relationship to a child, around 60% thought that the genetic link is simply one of the factor the court should consider in ordering residence, about 30% thought that it was not important at all, and 10% had the view that the genetic link was very important in deciding where the children should live.

CONCLUSION

Finally, the recent Supreme Court decision in Re B, reversing the decision of the Court of Appeal in granting a residence order in favour of a grandmother rather than the father, makes it clear that it is incorrect to refer to a presumptions or the right of a child to be cared for by its genetic parents and diminish the fundamental principle of the paramoutcy of the child’s welfare. The decision, in Re B reaffirms the principles of the Children Act 1989, however it did not clarify how much weight should be given to genetic parenthood. Thus poses the question of how much weight should be attached to it if the genetic relationship between parent and child if it ‘must count for something’ as stated by Baroness Hale? It could be suggested that the love and commitment given by an adult be it biological or non-biological parent to the child should be the most important factor in assessing where the child should reside. As the conducted survey suggests the ‘genetic link’ should not be the solely determined factor. Clearly, the current law on this area of law is inconsistent in the way in which it deals with non-genetic parents, as it could be seen above.

……..

About the Author- Maame Ankamaah-Fordjour is a Trainee Solicitor & JusticeGhana Youth-Editor

JusticeGhana

……..

Refrences

Available on Request