The Changing Boundaries of Indigenous Cultures

[The Republic v Trokosi, Ex parte The Child-Girls]ABSTRACT

One goal of the national constitutions and applicable human rights laws in many African countries, in the words of Bonny Ibhawoh, has been the establishment of a regime of minimal universal human rights standards founded on the diverse cultural and religious orientations of the people… is the tension and sometimes, contradictions between the national human rights standards of state law and policies on one hand and the objective social-cultural orientation of peoples on the other. Here, the tension and conflict between the constitutional guarantees of gender equality in national constitutions and the traditional status of women and child-girls in the context of invasive Trokosi cultural practice in some parts of Volta Region of Ghana, as it shall be shown, runs counter to not only the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, but also the national constitution, in that it encourages among others, early marriages, forced sexual intercourse and labour against its targeted victims- child-girls, and for that matter should have been condemned and purged by now. But as to how best to strike this delicate balance between the individual human rights standards guaranteed by the state and the collective cultural rights claimed by groups in Africa, here, Ghana, as Ibhawoh poses it, remain perhaps unfulfilled aspirations.

PART I

INTRODUCTION

Indeed indictment, to legal minds, is not verdict. It is a finger pointing, not judgement. This implies that the rules of natural justice require that our Brother, Robert Baker, must be fully heard before condemnation. But, when academic inquiry that borders contemporary human rights and freedoms, is regrettably reduced to religious beliefs and cultural relativism as it is being told and an attempt to find national solution to this alleged sexual-exploitation, becomes like Israelis/Palestinians asserting claims to the Holy Land through Torah and Koran, while their peoples seek shelter against raining bombs/missiles under glass houses and thatched tents, then undoubtedly early objection must be raised.

Throughout human history attempts have been made by philosophers, academics and politicians to define human rights, e.g. John Locke, Montesquieu, Thomas Hobbes and Thomas Jefferson and to add to the long list, Karl. Max. The Congress of Vienna of 1815 saw the Great powers accept an obligation to end the slave trade, which was finally abolished by the Brussels Convention of 1890, while slavery itself was formally outlawed by the Slavery Convention of 1926. The Hague Convention of 1907 and the Geneva Conventions of 1926, according to Chris Brown, were also designed to introduce humanitarian considerations in the conduct of war. The International Labour Office which was formed in 1901, and its successor the International Labour Organization, in the words of Brown, attempted to set standards in the workplace via measures such as the Convention Concerning Forced or Compulsory Labour of 1930

On the strength of inherent natural rights of every human being, indigenous scholar such John Mensah Sarbah, the leader of Aborigines Rights Protection, as its name implies and others defeated the Crown Bill that sought to overreach Gold Coast lands in 1898. The launching of National Congress of British West Africa in 1917, by indigenous son Casely Hayford, long before 1945 and third generation freedom fighters such as Dr J. B. Dankwa, Paa George Grant Nani Gbedemah and the other “Big Five”, show, perhaps, such yearn for mankind to be free.

Thus, the historical origins of power visions capable of shaping world events and attitudes like those of international human rights, did not fall like manner overnight but, in the words of P. G. Lauren, emerge in complicated and interrelated ways from the influence of many forces, personalities, and conditions in different times and diverse settings, each flowing in from its own unique way like tributaries into an ever larger and mightier river. Lauren has, My Brothers and Sister’s Keeper as his introduction chapter, and evokes the Biblical quotation in Genesis 49 (Am I my brother’s keeper?) to illustrate his argument. Indeed from Biblical Moses to the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the era of abolitionist William Wilberforce, mankind had always sought to be freed. So Lauren may be right when he proceeded that the international human rights at times, flow gently through the calm meadows of religious meditation, prophetic inspiration, poetic expression, or philosophic contemplation

For example, it was not until when the war allies realised the horrors of two world wars and the Holocaust that the UN adopt in 1948, the UDHR which, for the first time in history, according to Emeritus Professor Richard Falk- (professor of international law and practice at Princeton University and visiting professor of global studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, became the mother’s milk of the international community. Thus, international community had attempted to define a comprehensive code for the internal governance of its members which is based on the idea that individual [including for example, Trokosi child-girls and women], possessed rights simply because they were [are] human and that they should be internationally protected.

Modern thinking on human rights, in the words of Chris Brown, tends to distinguish between three generations of rights, first generation rights which encompass such rights as freedom of speech and assembly and second generation that captures economic, social and cultural rights not forgetting third generation rights, which concern the rights of ‘peoples’- our self-determination which we exploited for our independence. Yes, the Vienna Declaration for example, provides explicit thought for culture in human rights back-up and protection, stating that “the significance of national and regional particularities and various historical, cultural and religious backgrounds must be borne in mind”. However, Diana Ayton-Shenker submits that this is deliberately acknowledged in the context of the duty of States to promote and protect human rights regardless of their cultural systems. Thus, while its importance is recognized, cultural consideration, she argues, in no way diminishes States’ human rights.

Indeed, the problem with human rights these days, as Professor, Falk points out, is that it comes in more flavours like coffee or soft drinks. Thus, we may like the Asian, Islamic, indigenous, economic, European, or the U.S. version? So nation-states are true, at cross-roads when it comes to the question of compliance and enforcement of the UDHR and its subsequent conventions and protocols “How would we like our human rights to be served: with sanctions, regime change, corporate window dressing, or good old-fashioned moral suasion,” the emeritus professor quizzes.

There could be many reasons to this. But we are tempted to think that at the heart of this issue, are our relative culture and religious beliefs. As the emeritus professor argues, when the Declaration was discussed in 1948, 48 states voted for the Declaration, and eight abstained. The eight he says, included South Africa, whose white community at the time, was denying political rights. Thus, whereas the Soviet Union and its block abstained citing the lack of sufficient social and economic rights- being a second generation rights issue, Saudi Arabia froze on religious rights as the Declaration offer some religious ventilation- a third generation rights which, in the words of Professor Falk, they found it unacceptable, arguing that its people (the Saudis) were different from other peoples, therefore different rules should apply.

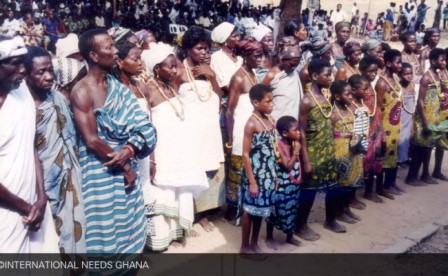

Photo Reporting- A community festival at Tsata-bame shrine. The shrine has now stopped taking trokosi but they are still able to perform their traditional religious practices. Proponents of the trokosi practice say that criminalisation of the practice is a loss of their cultural heritage.

The article: “Trokosi, Ewes And The Israelites”, in which Robert Baker represents “Trokosi child-girls as princesses fits perfectly into this category in that Robert attempts simply, to refute Broker and other researchers perceptions that these child-girls are more or less “sex-slaves.”. Indeed, it is from premise that perhaps, Professor Owusu-Ansah (of Lindsey-Wilson College, Columbia, Kentucky, USA) may be right when he argues that after decades of the abolition of slave trade, which still revives painful memories on the hearts and minds of people of African descent and eight years after Beijing- the signing and ratification of numerous conventions on the rights of the child and women by African nation, slavery still exists in a variety of forms as we continue to hurt our own kind and are ready to defend such actions on the strength of religion, partisan politics, patriarchal superstition, and to a greater extent, culture, which in the words of Brother Owusu-Ansah, more often than not, women and children are our victims, though the global thinking today is that slavery is dead?

Indeed, Africans could have shaken the dust under their feet, by embracing human rights, neo-liberal thinking that foster socio-economic development that the continent and most of its culturally incarcerated peoples, such as the Trokosi child-girl in rural Adidome (some 100 km, east of Accra), in the Volta region, trail. Pope John Paul II reminds us that the very progress of cultures demonstrates that there is something in [hu]man which transcends those cultures. This something, in the holy words of the late Catholic overlord, is precisely human nature which is itself the measure and the condition ensuring that man [woman] does not become the prisoner of any of his [her] cultures, but asserts his [her] personal dignity by living in accordance with the profound truth of his [her] being.

All the major religions of the world, writes Lauren, seek in or another to speak to the issue of human responsibility to others. Thus, despite their vast differences, complex contradictions, internal paradoxes, cultural variations, and susceptibility to conflicting interpretation and argumentation, all of the great religious traditions share a universal dissatisfaction with the world as it is and a determination to make it better by addressing the meaning of human life, the worth and dignity of all persons, and, consequently, the duty towards those who suffer… The source(s) of such duties more often than not transcend(s) arguably, ethnicity, religious or cultural beliefs and indeed, our immediate walls and frontiers. In that our own-self could be the abuser- here, the Trokosi fetish priest to the innocent Ghanaian child-girl.

Marcus Tullius Cicero is said to have argued in On the Laws that natural law founded ages before any written law existed or any state had been established, provided the source of “universal justice and law” for the world with direction to act justly and “be of service to others“. From this premise he reasoned that natural law “binds all human society together, applies to every member of the whole human race,” marks the unique dignity of each person, imposes on all of us responsibilities to be keepers of others, and provide “eternal and unchangeable law… valid for all nations and all. The preamble to the United Nations Charter, here, its second paragraph, reaffirms a ‘faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person (and), in the equal rights of men and women and nations large and small, likewise the provision in Article 55, which the UN is committed to promote, inter alia, ‘universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion, not forgetting Article 56, which all members of the UN pledge themselves to take ‘joint and separate action in co-operation with the UN for the achievement of the purposes set forth in Article 55.

Diana Ayton-Shenker argues that every human being has the right to culture, including the right to enjoy and develop cultural life and identity. However, cultural rights, our learned sister submits, are not unlimited but limited at the point at which it infringes on another human right. “No right can be used at the expense or destruction of another, in accordance with international law… cultural rights cannot be invoked or interpreted in such a way as to justify any act leading to the denial or violation of other human rights and fundamental freedoms”, she explains. Thus, claiming cultural relativism as an excuse to violate or deny human rights is an abuse of the right to culture. And that if cultural tradition alone governs State compliance with international standards, then widespread disregard, abuse and violation of human rights would be given legitimacy. Accordingly, when traditional culture does effectively provide such protection, then human rights by definition would be compatible, posing no threat to the traditional culture.

Admittedly, the Trokosi child-girl or woman, perhaps, faces no rusted razor blade or knife that might put her in immediate fear as in the case of Female Genital Mutilation victim (FGM) in some parts of Africa. What they go through, according to most academics and commentators are more of psychological and emotional torture. The World Conference on Human Rights, held in Vienna in June 1993, called for elimination of violence against women in public and private life; and all forms of gender bias and of any conflicts arising between the rights of women and the harmful effects of certain traditional or customary practices, cultural prejudices and religious extremism. Its preliminary report in 1994 (by the Special Rapporteur, Ms. Radhika Coomaraswamy), provides a definition of gender-based abuse as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats. This is reinforced in Article 2 of the Declaration, which identifies among others, female genital mutilation and other traditional practices harmful to women; non-spousal violence; and violence related to exploitation.

Baker argues forcefully in his article that our Ewe mothers and sisters who can not conceive to have their own children but believe in this religion consult the shrine and pledge to give their child-girl to the divinity or what he describes as the deity or Fiahidi- the spiritual king, which the unborn innocent child-girls become its princesses. It is unclear whether child-boys ever became victims to this as was the case of Biblical Samuel and Sampson or the Trokosi priests ever had Torah or Bible from which these girls, for example, are piously indoctrinated.

Unfortunately, we are less tutored on this to be able to tell our own unique stories about Trokosi cultural values to that International Needs Ghana (NGO) working tirelessly on behalf of our maimed Republic, and has also castigated it as “sexual slavery.” It must be told that The Vienna Declaration states in its first paragraph that “the universal nature” of all human rights and fundamental freedoms is “beyond question”. Thus, states could be liable as if they were the real culprits if they fail to take reasonable steps to create such a legal climate for its peoples- there could be no cultural shield. Yes, we would have exaggerated this point if it is to be submitted that this private-private abuse or practice is a state-sanctioned venture which generally, international human rights law abhors and for that matter is deeply concerned.

Thus, the subject of women’s rights, as our learned sister Evelyn A. Ankumah argues, should be of significance to politicians of African States [Ghana has many] who express the view that without development there can be no human rights, in that women form some 50% of the continent’s population. In our ever-shrinking world unlimited by space and time- cultural relativism could not be the answer to our mounting problems. Trokosi- that still holds some 10,000 women and child-girls as slaves, and International Needs Ghana, whose crusade (via various vocational training programmes) is at the forefront for their liberty, reflects the changing boundaries of indigenous cultures that the disciples of Trokosi and the state cannot ignore as we pride ourselves as people who have produced a General-Secretary to the UN.

PART II

SUMISSIONS

Since one Robert Baker’s argument reels on Biblical edifications written on paper but not on tablets, it must be inquired or established whether: (1) the Nation Israel still practices this culture; (2) whether Trokosi priesthood subscribes to Torah, the Holy Bible or the religious dress codes of the Jews; and (3) whether indeed Ghana has taken reasonable steps, in the fulfilment of its international obligations under the UDHR and its subsequent Protocols.

The hearing continues…

First published on 25 January 2007 at Ghanaweb