…A Comparative Study of Ghana’s Press Freedom and The Incitement to Genocide in Rwanda

Asante Fordjour

MEMO

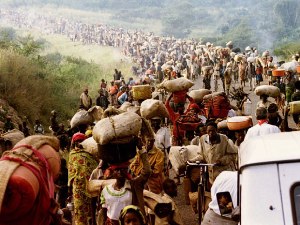

In December 2003, the judges at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) handed down its decision- convicting Hassan Ngeze, Ferdinad Nahimana, and Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, for *direct and public incitement to genocide. The three judges [from South Africa, Norway, and Sri Lankan], declared that: “Without a firearm, machete or any physical weapon, you caused the deaths of thousands of innocent civilians… Those who control the media are accountable for its consequences.” The prosecutors’ burden involved the interpretation of euphemisms- defined generally as harmless word/phrase that substitutes an offensive or suggestive one, to prove the “direct” nature of the incitement- such as the phrase “go to work” as a call to kill the Tutsi and the Hutu who opposed the then Rwandan regime. It was found that an individual or group who killed someone in response to [a] radio broadcasts or newspaper articles was not required to prove the incitement to genocide charge. In January 2007, the defence lawyers in the Rwanda “Media Trial” appealed the Tribunal’s decisions on various grounds. In its decision of 28 November 2007, the Tribunal affirmed the charge of “direct and public incitement to commit genocide” for Ngeze and Nahimana but reversed that of Barayagwiza. It ruled that only RTLM broadcasts made after 6 April 1994- when the genocide began, constituted “direct and public incitement to commit genocide,” as Barayagwiza no longer exercised control over the employees of the radio station at that time. He was however, charged for instigating the perpetration of acts of genocide and crimes against humanity. Because of the reversal of some of the charges against the convicts, the judges lowered the defendants’ sentences as follows: Nahimana’s from life to 30 years, Negeze’s from life to 35 years, and Barayagwiza’s from 35 to 32 years.

INTRODUCTION

On 9 December 1948, the United Nations approved the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, as an international crime which signatory nations “undertake to prevent and punish.” The Convention defines genocide to mean any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:(a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. The brainchild of this Convention is a Polish-Jewish lawyer- Raphael Lemkin, had argued in 1944 that the sufferings of the Jews during the holocaust had some semblance of these offences. The international community accordingly, accorded it with a legal backing so as to prevent future occurrence.

The Problem: Ghana in Context

At the ICTR trial, the judges highlighted important principles concerning the role of the media, which they said have not been addressed at the level of international criminal justice since the Nuremberg trials. The Tribunal accordingly, stated that “the power of the media to create and destroy fundamental human values comes with great responsibility.” In my judgement, and here, in the context of Ghana, it would be hypocrisy if we were to assume that Ghana deserves its global image as a promising test case of Africa’s democratic triumphs.

Our country, arguably, radiates all the unjustified political cultures and tensions that hamper not only inter-ethnic cohesion but also uneven socio-economic paradoxes that had plagued many nation-states into protracted conflicts and wars. The reintroduction of multi-party democracy in 1992 and all its associated ramifications- political and personal insults, not forgetting all forms of ethnic, religious, ideological, historical and economic biases and animosities, might have regrettably, prompted many of us to question whether multi-party democracy and its twin-pillar: free press and ideological tolerance, were best suited for the Ghanaian. Thus, democracy has brought us at cross-roads where the Ghanaian can without reservation, openly declare his/her hates towards a fellow countryman in a radio broadcast.

Then are, for example, phrases: “we the Akans- and all-die-be-die”, the terrifying Great Ashanti Project”, Voltarians should vote against the NPP to liberate themselves as a third class citizens, declaration of Jihad at Akwatia”, and more recently, the political tension at Odododoodio and its encountered declaration of war against Ewes and the Gas, are indeed, most unfortunate. Besides these had been the Ga-Adangbe youth’s or should I add, the Ga-Adangbe Council’s persistent attempts to revert the naming of the Accra Sports Stadium after Ohene Gyan, on the mere fact that Gyan is an [Akan] Akuapem but not a Ga-Adangbe?

The position of the Ga-Adange Youth on Kufuor’s bid to have an office in Accra, not forgetting the said posturing of the same group against the speculated attempt of the Asantehene to have a “palace complex” in Accra, illustrate the level of intolerance or ethnic suspicions that we hold against ourselves in this republic. Yet if any of these turbulences were to strike on the African in any of the western worlds or even in the Southern Africa, the equation would have been interpreted differently. No one is arguing that all these had just dropped from the heavens and without a cause. It is however, puzzling why all these are happening in such a magnitude under President Mills. Yes– from which authority did the so-called “foot-soldiers” manage to topple municipal/district chief executives from their posts?

Hate Speech, Falsehood and Incitement

If there could be anything that might likely derail Ghana’s current democratic gains, then it could be said that hate speech, falsehood and incitement, must be the feared. The crux of the Rwanda “Media Trial” which was opened on 23 October 2000 raises the issue of free speech rights. A key question, in the words of American lawyer and the case’s senior prosecutor for the Tribunal- Stephen Rapp, is what kind of speech is protected and where the limits lie. “It is important to draw that line. We hope the judgment will give the world some guidance,” he said. The question that should be occupying the hearts and minds of the Ghanaian Parliament and the public at large must be yes, the limits of democratic freedom.

We might have visited many reputable and indeed mushrooming websites. But we are yet to come across a media house- including radio and television stations, where the comments of its targeted audiences display sharp and indeed uncompromising political/ethnic divisions and suspicions of the nation-state that they represent. In 1997, ICTR indicted Ngeze who founded, published, and edited Kangura (Wake Others Up!), a Hutu-owned tabloid that in the months preceding the genocide published what ushmm.org forcefully describes as “vitriolic articles dehumanizing the Tutsi as inyenzi (cockroaches), though never called directly for killing them; and Nahimana and Barayagwiza, founders of a radio station- Radio Télévision Libre des Milles Collines (RTLM) that indirectly and directly called for murder, even at times to the point of providing the names and locations of people to be killed.”

The Part 3 of England, Wales, and Scotland, Public Order Act 1986 prohibits expressions of racial hatred, which is defined as hatred against a group of persons by reason of the group’s colour, race, nationality (including citizenship) or ethnic or national origins. Section 18 of the Act says: A person who uses threatening, abusive or insulting words or behaviour, or displays any written material which is threatening, abusive or insulting, is guilty of an offence if- (a) he intends thereby to stir up racial hatred, or (b) having regard to all the circumstances racial hatred is likely to be stirred up thereby. Offences under Part 3 carry a maximum sentence of seven years imprisonment or a fine or both. Yes, all are arguably, not roses here in the UK; yet it is safe to argue that the law offers some sort of ethnic cohesion.

The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 inserted Part 4A into the Public Order Act 1986. This prohibits anyone from causing alarm or distress. Part 4A states: (1) A person is guilty of an offence if, with intent to cause a person harassment, alarm or distress, he- (a) uses threatening, abusive or insulting words or behaviour, or disorderly behaviour, or (b) displays any writing, sign or other visible representation which is threatening, abusive or insulting, thereby causing that or another person harassment, alarm or distress. A person guilty of an offence under this section is liable on summary conviction to imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months or to a fine not exceeding level 5 on the standard scale or to both. Consider how many people would be affected if this law were to be applied in Ghana.

Although without freedom of speech and of the press, there could be arguably, no effective democracy. Yet has unqualified free speech not become breeding grounds for propagation of falsehood and unjustified finger-pointing on our airwaves and print media which seem to deepen ethnic and political passions and misconceptions? To address some of these issues in the UK, Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 amended the Public Order Act 1986 by adding Part 3A which states: “A person who uses threatening words or behaviour, or displays any written material which is threatening, is guilty of an offence if he intends thereby to stir up religious hatred.” Yes- the Part 3A protects freedom of expression by stating in S.29J that:

Nothing in this Part shall be read or given effect in a way which prohibits or restricts discussion, criticism or expressions of antipathy, dislike, ridicule, insult or abuse of particular religions or the beliefs or practices of their adherents, or of any other belief system or the beliefs or practices of its adherents, or proselytising or urging adherents of a different religion or belief system to cease practising their religion or belief system. The Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008 amended Part 3A of the Public Order Act 1986. In keeping track with global trends, the amended Part 3A adds, for England and Wales, the offence of inciting hatred on the ground of sexual orientation. Thus in the UK unlike in the Republic of Ghana, it is illegal to incite against homosexuals! Part 3 offences attach the following acts:

The use of words or behaviour or display of written material, publishing or distributing written material, the public performance of a play, distributing, showing or playing a recording, broadcasting or including a programme in a programme service, and possession of inflammatory material. In relation to an alleged hatred based on religious belief or on sexual orientation, it is suggested that the relevant act- here, words, behaviour, written material, or recordings, or programme- must be threatening and not just abusive or insulting. Besides “hate speech” laws, the United Kingdom has also hate crime laws. For England, Wales, and Scotland, the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 makes hateful behaviour towards a victim based on the victim’s membership (or presumed membership) in a racial group an “aggravating factor” for the purpose of sentencing in respect of specified crimes.

Specified crimes are assault, criminal damage, offences under the Public Order Act 1986, and offences under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997. A “racial group” is a group of persons defined by reference to race, colour, nationality or citizenship, ethnic or national origins. So what could this mean: “Today I declare war in this country…Gbevlo-Lartey and his people, IGP should know this: Voltarians in the Ashanti Region will not be spared…. If anyone touches you, butcher him with a cutlass…” Who touches who? The said “fake policeman or woman” who might not necessarily be a Ga or an Ewe? What about restricting the voting registration rights of those who do not look like us with our blood? Hate speech and incitement come in many forms.

In Trial Judgment in the case of Prosecutor v. Simon Bikindi (ICTR 2 December 2008), Bikindi- a famous and distinguished Rwanda composer and singer, was indicted for inciting ethnic passion in the run-up to the 1994 genocide by using his music and fame to drum up support for the Hutu-led regime, and by fostering ethnic hatred throughout the carnage. He was also held accused of incitement for composing and performing songs like Nanga Abahutu (“I Hate These Hutu,” an anti-Tutsi song). According to prosecution witnesses who appeared before the ICTR, Bikindi’s song was not only an invitation to hate Tutsi, but given the context of the ongoing civil war, to be ready to kill them as well. Although the Trial Chamber is said not to have been persuaded that his songs amounted to incitement to commit genocide, the judges however, convicted him for statements that he made via loudspeaker- in the Rwandan countryside during the genocide. Bikindi was accused of asking his audiences, among other things: “Have you killed the Tutsi here?” and referred to Tutsis as “snakes.”

The Bikindi case is describes as an illustration of sophisticated understanding of cultural context- notably linguistic usage and subtlety- critical for the legal determination of the directness of any alleged incitement to genocide. Ushmm.org contrasts this decision to the prosecution of genocide at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in The Hague as the prosecution of atrocities other than genocide, predominated the proceedings. There it is argued that mass communication, was used mainly for spewing hate propaganda, rather than incitement to commit genocide as defined in strictly legal terms.

International Law in Context

Article III (c) of the Genocide Convention declares that “direct and public incitement to commit genocide” is a crime. In the Rwandan case, “incitement” was held to mean any act employed to encourage or persuade another to commit an offence by way of communication- for example, broadcasts, publications, drawings, images, or speeches. According to ushmm.org, the offence is “public” under international law if it is communicated to a number of individuals in a public place or to members of a population at large by such means as the mass media. Thus, among other things, its “public” nature distinguishes it from an act of private incitement- which as the authors argue, could be punishable under the Genocide Convention as “complicity in genocide” or possibly not punishable at all. In other words, incitement to genocide must also be proven to be “direct,” meaning both the speaker and the listener, understand the speech to be a call to action.

Yet it is suggested that prosecutors, have found it challenging to prove what “direct” may mean in different cultures, as well as its meaning to a given speaker. Thus public incitement to genocide can be prosecuted even if genocide is never perpetrated. Therefore, lawyers classify the infraction an “inchoate crime”: and that proof of result is not necessary for the crime to have been committed, only that it had the potential to spur genocidal violence. Thus it is the intent of the speaker that matters, not the effectiveness of the speech in causing criminal action. This prompted the introduction of the 1998 incitement provision to be included in Article 25(3)(e) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

SUBMISSION

In this article we have attempted to show that free press comes with domestic and global responsibility which as far as international justice is concerned, cannot be bought and sold with ethnic, political or national colours. JusticeGhana appeals therefore, to Parliament to enact enabling law that cleans up not only our airwaves or print media but also protects all sections of our communities which indeed included the lawless Fulani herdsman or woman.

Asante Fordjour is the Director of Legal & Media Research, JusticeGhana Group, United Kingdom

JusticeGhana.com