Welcome

....to JusticeGhana Group

JusticeGhana is a Non-Governmental [and-not-for- profit] Organization (NGO) with a strong belief in Justice, Security and Progress....” More Details

The Promises of Ghana-Ivorian Maritime Rifts

- Details

- Category: International Justice

- Created on Wednesday, 13 May 2015 00:00

- Hits: 9808

The Promises of Ghana-Ivorian Maritime Rifts

The Promises of Ghana-Ivorian Maritime Rifts

…International Maritime Law in Context- The Pro-Equidistance and Equitable Principles Examined

BRIEFS & MEMOS (PART I of II)

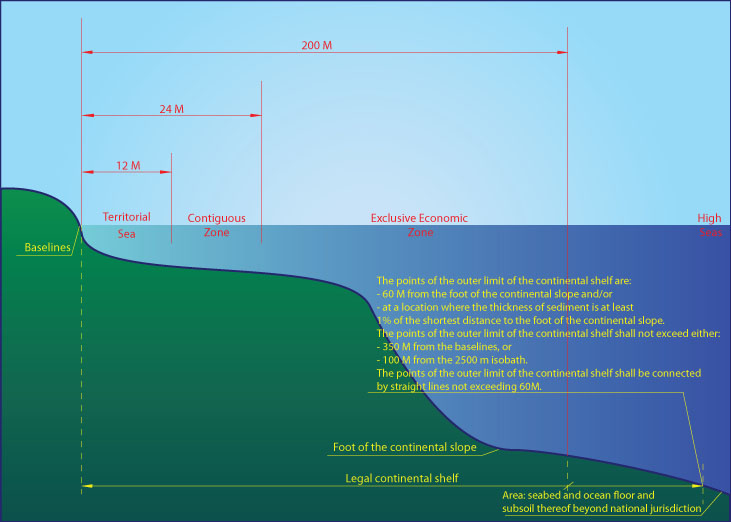

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), known otherwise as the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea treaty is an international agreement that resulted from the Third “Conference” adopted on 29 August 1980, a “Statement of Understanding” which is contained in Annex II to the Final Act of the Conference, addressing among others, issues concerning the definition of the continental shelf (CS) and the criteria by which a coastal State may establish the outer limits of its continental shelf are set out in Article 76 of the Convention [1]. The term “continental shelf” is used by geologists generally to mean that part of the continental margin which is between the shoreline and the shelf break or, where there is no noticeable slope, between the shoreline and the point where the depth of the *superjacent water is approximately between 100 and 200 metres. However, this term is used in article 76 as a juridical term [1]. According to the Convention, the continental shelf of a coastal State comprises the *submerged prolongation of the land territory of the coastal State – the *seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas that *extend beyond its territorial sea to the outer edge of the continental margin, or to a distance of *200 nautical miles (NM) where the outer edge of the continental margin does *not extend up to that distance. The continental *margin consists of the seabed and subsoil of the shelf, the slope and the rise. It does not include the deep ocean floor with its oceanic ridges or the subsoil thereof. According to article 76, *the coastal State may establish the outer limits of its juridical continental shelf wherever the continental margin extends beyond 200 nautical miles by establishing the foot of the continental slope, by meeting the requirements of Art 76, paragraphs 4 – 7, of UNCLOS [1]

INTRODUCTION

The recent *delimitation dispute involves Bangladesh/Myanmar. Under UNCLOS, States are permitted to submit maritime disputes not only to the ICJ and to arbitration (see, UNCLOS Annex VII and VIII) and the ITLOS.) Commenting on this case, Herbert Smith Freehills Arbitration [2] notes that despite the prominent role it has been given under UNCLOS in interpreting and enforcing rights and obligations under UNCLOS, many of the cases before the ITLOS in its legal history, have concerned prompt release of vessels, and to a lesser degree fishing issues (particularly of swordfish and southern blue fin tuna). “Whilst it was common ground between the Parties that the territorial sea (12 nautical miles (“NM“)) and the exclusive economic zone (“EEZ“) and “inner” continental shelf (up to 200 NM) *should be delimited by the ITLOS, there was considerable debate as to whether (i) the ITLOS had jurisdiction to delimit the continental shelf beyond 200 NM and, (ii) if so, whether it should exercise that jurisdiction.”

BACKGROUND

On 27 February 2015, La Côte d’Ivoire, filed an application for provisional measures at the Special Chamber in Hamburg, requesting the Germany-based Maritime Tribunal, to prescribe provisional measures requiring Ghana to: (1) take all steps to suspend all ongoing oil exploration and exploitation operations in the disputed area; (2) refrain from granting any new permit for oil exploration and exploitation in the disputed area; (3) take all steps necessary to prevent information resulting from past, ongoing or future exploration activities conducted by Ghana, or with its authorization, in the disputed area from being used in any way whatsoever to the detriment of Côte d’Ivoire; (4) and, generally, take all necessary steps to preserve the continental shelf, its superjacent waters and its subsoil; and (5) desist and refrain from any unilateral action entailing a risk of prejudice to the rights of Côte d’Ivoire and any unilateral action that might lead to aggravating the dispute. Ghana opposed this at the public hearing, requesting “the Special Chamber to deny all of Côte d’Ivoire’s requests for provisional measures.” [3]

In its preliminary ruling of Saturday, 25 April 2015, concerning the rights which Côte d’Ivoire claims on the merits and seeks to protect, the Germany-based Special Tribunal stated that, before prescribing provisional measures, it needs only satisfy itself that these rights are at least plausible (paragraph 58) and finds that Côte d’Ivoire has presented enough material to show that the rights it seeks to protect in the disputed area are plausible (paragraph 62). Pursuant to Article 290 of “the Convention” the Special Chamber ((Case No. 23 (Provisional Measures)) considered an order suspending all exploration or exploitation activities conducted by or on behalf of Ghana in the disputed area, including activities in respect of which drilling has already taken place, would cause prejudice to the rights claimed by Ghana and create an undue burden on it and that such an order could also cause harm to the marine environment (paragraphs 100 and 101). The Special Chamber unanimously, requests each Party, to submit to the Special Chamber the initial report referred to in paragraph 105 not later than 25 May 2015, and authorizes the President of the Special Chamber, after that date, to request such information from the Parties as he may consider appropriate after that date, adding, each Party shall bear its own costs [3].

Professor Kwame Fordjour Mfodwo- the National Coordinator for the Ghana Maritime Boundary Secretariat, is quoted to have told Samson Lardy Anyenini, on Joy FM and MultiTV’s news analysis programme that the ITLOS ruling on an application for provisional measures brought by the Ivorians, shows clearly that “what we said belongs to us, [actually] belongs to us.” Many Ghanaians think that success could be for the country so there is no need for any negotiations. [4] Yet, the law of the sea, according to Nugzar Dundua, is a difficult and multiform branch of law, which comprises the norms regulating the rights and obligations of States in the marine area and not as simple as we might think? Scarcity of land-based natural resources and heightened economic interest have complicates matters. [6]

Then are scientific and technological inroads which had also shown the potential importance in this respect of the natural resources of the continental shelf. So it is not surprise when on 30 March 2015, Ghana’s Attorney-General and Minister for Justice- Marietta Brew Appiah-Opong submitted on behalf of the Republic, to the Hamburg-based Chamber, denying all claims being made by Ivory Coast. Yet it is unclear by what authority is Ghana prophesying legal victory. Delimitation by agreement remains the primary rule of international law and that the negotiating process is crucial for achieving agreement and the process must be effected by agreement between parties as recognised by the 1982 LOS Convention.

Per Dundua [6], maritime zones of two States frequently meet and overlap, and the line of separation has to be drawn to distinguish the rights and obligations between the States and delimitation is a process involving the division of maritime areas in a situation where two (or more) States have competing claims. Some of the referred complexities of the delimitation process are set here as follows: (1) the source of authority; (2) issue involves the principal methods by which it is carried out, and (3) technical questions regarding the determination of the actual lines in space. [7] Yes, Prescott and Schofield [8] argue that these can be viewed as an essential precursor to the full realisation of the resource potential of national maritime zones and the peaceful management of the oceans and seas and with regard to the seabed resources, which could prove crucial to the well-being and political stability of coastal States, extensive overlapping claims forestall development while maritime boundaries remain unsettled. [8]

The next part considers this dispute in the light of case studies on the emergence of the equidistance principle as a method of delimitation in early treaty law, such as in the 1958 Conventions, and reflect for example, on the case involving adjacent States in 1982, concerning the delimitation of the CS between Tunisia and Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, where the two parties asked the Court to clarify what are the principles and rules of international law which may be applied for the delimitation of a CS between two States. We shall consider relevant circumstances, as well as recent trends admitted at UNCLOS III and how parties had requested the Court to show the practical way on how to apply the indicated rules and principles so as to enable the experts of the two States to delimit those areas without any difficulties.

…Mtf

Asante Fordjour LLB (Hons) LLM Int’Law And Criminal Justice, authored this article.

JusticeGhana

………….

References Available On Request