Welcome

....to JusticeGhana Group

JusticeGhana is a Non-Governmental [and-not-for- profit] Organization (NGO) with a strong belief in Justice, Security and Progress....” More Details

The Prophecies Of Ghana-Ivorian Dispute - CASE STUDY

- Details

- Category: International Justice

- Created on Sunday, 10 May 2015 00:00

- Hits: 12096

CASE STUDY

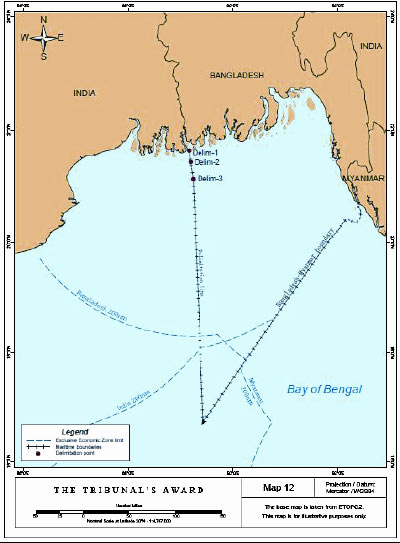

After years of negotiations and despite many no final delimitation agreement was agreement over their maritime boundary in the Bay of Bengal, the ITLOS, on 14 March 2012, issued its judgment in the dispute between Bangladesh and Myanmar- both parties to UNCLOS, in the Bay of Bengal. Relations became strained in October 2008 when survey ships subcontracted by Daewoo, and acting under licence from Myanmar, began conducting survey work close to St Martin’s Island and in a maritime area claimed by Bangladesh. In that case, Bangladesh responded by dispatching three naval vessels leading to a stand-off between the two navies lasting over a week until the Daewoo vessels withdrew [2]. Without much time to spend on the case history let us consider what had been told about this landmark decision:

After years of negotiations and despite many no final delimitation agreement was agreement over their maritime boundary in the Bay of Bengal, the ITLOS, on 14 March 2012, issued its judgment in the dispute between Bangladesh and Myanmar- both parties to UNCLOS, in the Bay of Bengal. Relations became strained in October 2008 when survey ships subcontracted by Daewoo, and acting under licence from Myanmar, began conducting survey work close to St Martin’s Island and in a maritime area claimed by Bangladesh. In that case, Bangladesh responded by dispatching three naval vessels leading to a stand-off between the two navies lasting over a week until the Daewoo vessels withdrew [2]. Without much time to spend on the case history let us consider what had been told about this landmark decision:

It strengthens the three-stage delimitation method expounded in the Black Sea case; It began a new chapter in the law on maritime boundary delimitations by delimiting the Outer Continental Shelf’ (OCS); It reinforced the notion that in law there is only a single continental shelf and that there is no difference in the application of Law on Sea Convention (LOSC) Article 83 within or beyond 200 nm; and that the delimitation of the OCS and the delineation of its outer limits are separate procedures. This involves three separate stages:- First, drawing a provisional equidistance line based on the geography of the States’ coasts; and Second, asking whether there were any “relevant circumstances” which required that line to be adjusted to allow for an equitable result; and finally, applying the “test of disproportionality“. After constructing the provisional equidistance line, Bangladesh’s “manifestly concave” coast line was a “relevant circumstance” which necessitated adjustment of that provisional equidistance line. [12]

Concavity will not always be taken into consideration, but “…when an equidistance line drawn between two States produces a cut-off effect on the maritime entitlement of one of those States, as a result of the coast, then an adjustment of that line may be necessary in order to reach an equitable result.” [2] However, it did not consider that St Martin’s Island, a “significant maritime feature by virtue of its size and population and the extent of economic and other activities“, which the ITLOS had awarded its own 12 NM territorial sea, warranted an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line; nor would the Bengal depositional system, being the “physical, geological and geomorphological connection between Bangladesh’s land mass and Bay of Bengal” be a relevant circumstance to be taken into consideration either. The ITLOS then endorsed the third stage in the methodology for maritime delimitation. At this third stage, a tribunal must ascertain whether the delimitation line leads to “an inequitable result by reason of any marked disproportion” between the ratio of the relevant coastal lengths and the maritime areas of the respective States parties. This tends to be a fairly general test that one side has not been treated inequitably, rather than a substantive analysis of whether a ratio is “proportionate“.

The ITLOS has noted that, “mathematical precision is not required“. After deciding that the scientific evidence presented by Bangladesh did not prevent Myanmar making a claim to the outer part of the continental shelf, the ITLOS found that no further adjustment to the equidistance line was necessary: the ratio between the total areas awarded and the ratio of the respective lengths of Bangladesh and Myanmar’s coastlines were not disproportionate. It is suggested that the ITLOS’s judgment helps to clarify some of the issues at stake including the sovereign rights of a large area of the EEZ and continental shelf of the Bay of Bengal. These are directly relevant to the rights of Bangladesh and Myanmar to grant hydrocarbon exploration and production rights in those areas and will give comfort to oil companies such as ConocoPhillips, Tullow and Daewoo who have interests there. [2]

Yet for all the clarity of the judgment, Herbert Smith Freehills Arbitration argues, uncertainties remain: First, a small “grey area” within 200 NM of the Myanmar coast, but on the Bangladesh side of the delimitation line, was not delimited by the ITLOS. Thus “after considering the difficulties it presented, the ITLOS instead noted that there existed many ways for the parties to reach an agreement on this limited area, hinting perhaps at joint development or unitisation. Second, the adjusted equidistance line extending beyond 200 NM plotted by the ITLOS does not have a terminus point – it is said to continue “until it reaches the area where the rights of third party States may be affected.” That those rights remain a live issue and that the status of India’s substantial claims within the Bay of Bengal remains very much unsettled. As noted by the ITLOS, its judgment does not bind third-parties such as India (which is currently engaged in arbitral proceedings of its own with Bangladesh) and its delimitation is without prejudice to the delineation of the continental shelf to be decided upon by the CLCS. [2]

The Prophecies of Ghana?

In 2002, the ICJ gave judgment on the maritime boundary between two adjacent States- Cameroon and Nigeria. [13] The States asked the Court to draw a single maritime boundary for each respective zone. The parties also agreed upon the method of delimitation: to draw an equidistance line and then consider whether there are factors calling for adjustment of that line to achieve an equitable result. [Ibid. P. 4.] But the States disagreed about the existence of special circumstances necessary for the shifting of equidistance line. Relying on its earlier authorities judgment, the Court “made it clear what are the applicable criteria, principles and rules of delimitation” for a single maritime boundary which “are expressed in the equitable principle/relevant circumstances method […] which is very similar to the equidistance/special circumstances method applicable in delimitation of the territorial sea.” [Ibid. Par. 88.] Beyond the territorial sea, the Court referred to the case between Qatar and Bahrain, [14] where it had stated that […] for the delimitation of maritime zones beyond the 12 mile zone it would first provisionally draw an equidistance line and then consider whether there were circumstances which must lead to an adjustment of that line. The Court found it convenient in applying that rule. [Ibid, 14, Par.289]

For the delimitation of the territorial Sea the Court considered that there existed a valid international agreement between the States, [Ibid. Par. 263] – leaving it with the delimitation of the EEZ and CS of the respective States. Before drawing the equidistance line, the Court found it crucial to define the relevant coastlines and the location of the base points for the construction of that line. [Ibid. Par. 290-292] It looked first for the existence of geographical circumstances- rejecting Cameroon’s position regarding the concavity of its coastline as a special circumstance for the modification of the equidistance line as relevant coastlines for the delimitation already determined by the Court. It noted: “sectors of coastline relevant to the present delimitation exhibit no particular concavity” [Ibid. 14, Par. 297], as the concave sector of Cameroon’s coast was outside the delimitation area.” The Court did not also regard the presence of the Bioko islands as a circumstance justifying the shifting of the equidistance line, stating the island did not belong to either of the States party to the dispute. [Ibid. Par. 299]

In 1984, an ICJ Chamber was requested by two adjacent States, the USA and Canada, to draw a single maritime boundary in the Gulf of Maine for both the continental shelf and fishery zones. [15] The Chamber was confronted with the following: “what is the course of the single maritime boundary that divided the continental shelf and fisheries zone between the respective States.” [16] In its submission, Canada invoked the application of the equidistance line based on Article 6 of the 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf, which was in force for both States. Canada submitted that equidistance/special circumstances method should be applied as a treaty rule for the CS and as a general norm for the delimitation of the adjacent fishery zone. The Chamber said as treaty law for the CS this principle could be valid, but to accept the latter […] would amount to transforming the combined equidistance/special circumstances rule into a rule of general international law, and thus on capable of numerous application, whereas there is no trace in international custom of such transformation having occurred. [17]

The Chamber also pointed out that equidistance […] cannot have such mandatory force even between States which are parties to the convention, as regards to a maritime boundary concerning a much wider-subject than the continental shelf alone. [Ibid. Par. 124.] The Chamber also took into account the view expressed in the 1969 North Sea case, that equidistance was not a principle of customary international law (see, the 1982 Tunisia/Libya case and the two adjacent States Case of Guinea and Guinea-Bissau, 18 February 1983), where whether the Convention of 12 May 1886 between France and Portugal and the protocols annexed to that Convention established the maritime boundary between the respective States and in which Guinea-Bissau raised equidistance, might be relevant. It argued that the coast of the two States are opposite and the preference for equidistance was found in the argument that equidistance faithfully reflects the coastal configuration and complies with the requirements of the equitable principle not to refashion nature. It also acknowledged that the existence of special circumstances might lead to an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line. [18]

The Tribunal itself considers that the equidistance method is just one among many and there is no obligation to use it or give it priority, even though it is recognised as having a certain intrinsic value because of its scientific character and the relative easy with which it can be apply. After carefully examining the general direction and configuration of the coastline, the Tribunal observed the existence of special circumstances, such as the concave coasts of the States, if taken the whole configuration of the West African coast and the presence of some islands. Taking into account these circumstances and the situations of adjacency, it rejected to apply the equidistance method, as it would yield an inequitable result. [18] In 2002, the ICJ gave judgment on the maritime boundary between two adjacent States of Cameroon and Nigeria. Applying the Guinea-Bissau reasoning the Court said that “[…] for the delimitation of maritime zones beyond the 12 mile zone it would first provisionally draw an equidistance line and then consider whether there were circumstances which must lead to an adjustment of that line.” [19] For the delimitation of the territorial sea, the Court found valid international agreement between the States- leaving it with the delimitation of the EEZ and CS of the States Parties.

CONCLUSION

So what could be the prophecies of this “go-to-court-go-to-court Ghana-Ivorian Rifts be? In this article, we have sought to consider the following: (a) Geology and geomorphology; (b) Socio-economic circumstances; (c) Conduct of the States; (d) The interest of third States and security (political) consideration; and (e) Historic title. It also acknowledged that the existence of special circumstances might lead to an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line. But empirical case studies also illustrate that after carefully examining the general direction and configuration of the coastline, a tribunal might acknowledge the existence of special circumstances, such as the concave coasts of the States, if taken the whole configuration of the West African coast and the presence of some islands. The promises or the prophecies are that taking into account these circumstances and the situations of adjacency, a Maritime Special Court had also rejected to apply the equidistance method, as it could yield an inequitable result.

Asante Fordjour LLB (Hons) LLM Int’Law And Criminal Justice, authored this article.

JusticeGhana

………….